rd.com June 2014

Deeply troubled by the reports of violence against the Jews in Europe, Gil Kraus decided to rescue children from the clutches of Nazi Germany, his posh home and successful law practice in Philadelphia treasures he could let go. Even with two kids, 13 and 9—and perhaps because of them—he was willing to confront danger for families suffering terror. Won over to his vision, his wife Eleanor prepared affidavits from people who signed on to help support the kids financially. When she was kept from joining him on the voyage to Europe, Gil convinced their friend and children’s pediatrician Dr. Robert Schless to take her place. The men found themselves in Austria which, swept into the Third Reich, saw Jews by the tens of thousands in a panic to flee. At Gil’s urging, Eleanor caught the next ship out across the Atlantic.

rd.com June 2014

Austrian Jews streamed to give their children up to the couple, fully aware they might never see their precious ones again. Eleanor wrote: “Yet it was as if we had drawn up in a lifeboat in a most turbulent sea. Each parent seemed to say, Here, yes, freely, gladly, take my child to a safer shore.” The most agonizing part was choosing whom to save. Dr. Schless advised caution, as any sick child would be refused at the doors of Immigration, and the children needed to be mature enough to endure the separation from their parents. Hoping for 50 visas from the American embassy in Berlin, the Krauses along with Dr. Schless finalized their selection of the kids, ages five to fourteen. “Their eyes were fixed on the faces of their children, Eleanor remembered of the parents later. Their mouths were smiling. But their eyes were red a fnd strained. No one waved. It was the most heartbreaking show of dignity and bravery I had ever witnessed. Almost a third got visas and later reunited with their children.” (Reader’s Digest excerpt of Steven Pressman’s 50 Children: One Ordinary American Couple’s Extraordinary Rescue Mission into the Heart of Nazi Germany.)

50 Children by Pressman

About half the children are still alive, now elderly. With the support of counselors and medical staff, and some with their parents, the young emigrants seized the lifeline of a new language and culture. Fear gave way to hope, hope answered by achievement. When these teachers, doctors, writers, business executives found love, they became parents, grandparents, great-grandparents. Their lives, in other words, meant the lives of many others. This, despite the stringent refugee quota and unconcealed antiSemitism in the U.S. State Department, thanks to the startling sacrifices of three Americans to whom their own lives meant more than personal comfort and safety.

Fast-forward 25 years, the law that would determine my own place in the world before I was born:

This measure that we will sign today will really make us truer to ourselves both as a country and as a people. It will strengthen us in a hundred unseen ways. This system [that] violated the basic principle of American democracy the—principle that values and rewards each man on the basis of his merit as a man…is abolished…We can now believe that it will never again shadow the gate to the American Nation with the twin barriers of prejudice and privilege…The dedication of America to our traditions as an asylum for the oppressed is going to be upheld. (Lyndon B. Johnson, as he signed the The Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 that opened America’s doors to Asia, Africa, Latin America.)

Fast-forward 50 years. The man who campaigns to build a wall and protect the nation’s borders wins the presidency.

The exuberant response to the election results among some families I know brought about a revelation for me. Though they have been polite, some even kind, I had not noticed the white bubble that floats them from activity to activity, a way of life I find unnatural in diverse Southern California. But then again, I thought, aren’t these Caucasian families entitled to keep the company they wish? I was reminded of the way Korean-Americans manage to find their own in every large city. And there are the Chinese and Indian and every other ethnic group. Take a mélange of people, and we don’t disperse like marbles you shake in the jar. No, multiculturalism doesn’t work that way. The marbles organize themselves, often by color: NYC’s Chinatown, Koreatown, Little Italy. Sure, we build cross-cultural friendships. The marbles mix. But cultures will always build their own communities. This is one way those who interface the white mainstream as outsiders maintain their blood identity. So it jarred me to see white people enjoying life in their happy sac. It meant they were content to keep outsiders…outside.

But I get it. If I had grown up on Wisconsin cheese, if my grandparents and great-greats were all white, I wouldn’t be necessarily racist for not flinching at threats against immigrants. After all, these are other people. Not the ones you have Bible Study with, the ones your kids have sleepovers with, not the friends you gather over a latte. They are characters in the margins of your life, the check-out girl at Walmart you don’t really look at, the day laborers you drive past in the rain, extras moving as on a reel. They are center stage only on TV and the news.

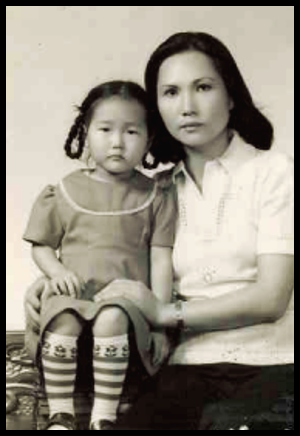

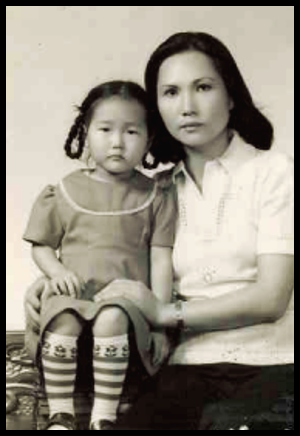

Passport Photo, 1977: The Little Wayfarer Sets Out

And when you watch us Asian-Americans kick butt in school, take the stage with our awards.

Except the mentality of Other was the long sleepy response of the masses to word of Hitler’s brutality overseas. After all, America had problems of its own. And to this day, claiming American citizenship remains a privilege and a problem. Let’s start in our backyard, the detritus we never cleaned up. In all the talk about race, we rarely hear about the Native Indians anymore, and that’s because they are going extinct from war, disease, emigration, and eradication of their culture. The Navajo reservation in Arizona my church has visited remains worse off in crime and poverty statistics than those of our inner cities. The country that built itself on the bleeding backs of slaves grew on the sweet milk of bigotry and contempt for anyone who was not white. This included all “Asiatics” like the Chinese who laid the rails to unite the states of America. The largest mass lynching in U.S. history was not of blacks but the Chinese in the massacre of 1871 in Los Angeles. We also remember the Japanese-Americans, uprooted and packed away in camps during the Second War.

Let me put down the textbook and pick up my journal. Both my father and younger brother have been mugged at knifepoint and my mother spit on at the deli we owned in Queens, New York. On the other coast in 1992, my aunt watched the flames engulf her store in the LA Riots, the work of black arsons. America picked its way through the racial degradation and rose to its feet as a single country, not by skyscrapers but by the brick and mortar of dry cleaners, shops, restaurants, the acquiescence of immigrants who did whatever it took because hard work was not an option. The dirt and concrete just fertile soil for dreams, their Korean sons and daughters, for one, conquered the best schools. Harvard Law. Stanford School of Business. Columbia. M.I.T. If Trump had been President in 1965, he would not have welcomed the little girl with pigtails from Seoul, Korea—though he hails from immigrants just the same. In any case, I don’t apologize for having come. Somebody has to watchdog the English grammar in this country. I have taught children of all class and color how to write, and write well, figure numbers with ease, give speeches, write poetry, seek beauty. My Asian-American friends have bettered hospitals, furthered academia, moved Wall Street, planted churches, fed the homeless. Our commitment to excellence, intelligence, the drive with which we have emulated our parents served not only our secrets dreams but our country. This work ethic and hope in freedom have forged America, generation after generation, filled and cemented the fissures of mistrust between disparate cultures as we did business together, advanced the economy together with the currency of respect. This, Mr. President, is how we have helped make America great.

And friends, free market to me doesn’t mean billionaires or corporate executives first. It means customer first. I come to the table every time expecting the type of service and dedication my parents and I put in whenever, wherever we were up at bat. And if you don’t come through, I open my purse elsewhere and you will learn to do better. Free market means choice and choice means you had a chance. It’s not always front and center but in this country, the holy grail of opportunity awaits the thirsty and the earnest. Resourcefulness always finds room, a corner it can turn. And if you can’t move the boulder somebody put in your way, you can raise that strong, beautiful voice you claimed at birth. I honestly believe those feeling trapped can look up and find open sky. At least they could, once.

I am not saying we have to answer every country’s knock and plea. A group is only as strong as its weakest members, at least how well the other parts can compensate for them. And yes, turning the country into an international homeless shelter creates some serious socioeconomic complications. But to lock the pearly gates and do an about-face while humanity perishes behind our back hardly makes for world leadership. Don’t make it a zero-sum game, and don’t spew hateful rhetoric in the name of patriotism. History asks America to renew its vows to liberty and justice, which we now look about to abdicate.

There they stand, the good, bad, and the ugly, the many faces of the most powerful nation in the world. The heterogeneous richness, opportunity, support, competition, hypocrisy, oppression. This April marks for me and my parents 40 years in this country. English may be my second language, but this land will always be my home. Because it’s simple. I am America.

I'd love to share this on my network.

I was crossing a rough set of tracks in a 28-wheel diesel truck in October of 2013 when to my astonishment and fear, the crossing gates suddenly dropped, the reds lights began flashing, and the warning bells rang. With not even time to think, all I could do was tighten my grip on the steering wheel. I watched the train come at me before I heard the metal on metal and felt the impact. Everything slowed to a deafening silence and darkness.

I was crossing a rough set of tracks in a 28-wheel diesel truck in October of 2013 when to my astonishment and fear, the crossing gates suddenly dropped, the reds lights began flashing, and the warning bells rang. With not even time to think, all I could do was tighten my grip on the steering wheel. I watched the train come at me before I heard the metal on metal and felt the impact. Everything slowed to a deafening silence and darkness. Making my way through 24 specialists, I was diagnosed with anxiety, depression, PTSD, nerve damage, and chronic back and neck pain. I went from being healthy and active to depending on a cocktail of sixteen drugs: pain meds, psychiatric meds, muscle relaxers, sleep meds.

Making my way through 24 specialists, I was diagnosed with anxiety, depression, PTSD, nerve damage, and chronic back and neck pain. I went from being healthy and active to depending on a cocktail of sixteen drugs: pain meds, psychiatric meds, muscle relaxers, sleep meds.